This post serves as first discussion regarding a proof of concept for what I believe is a proper way to design and manage machine learning pipelines.

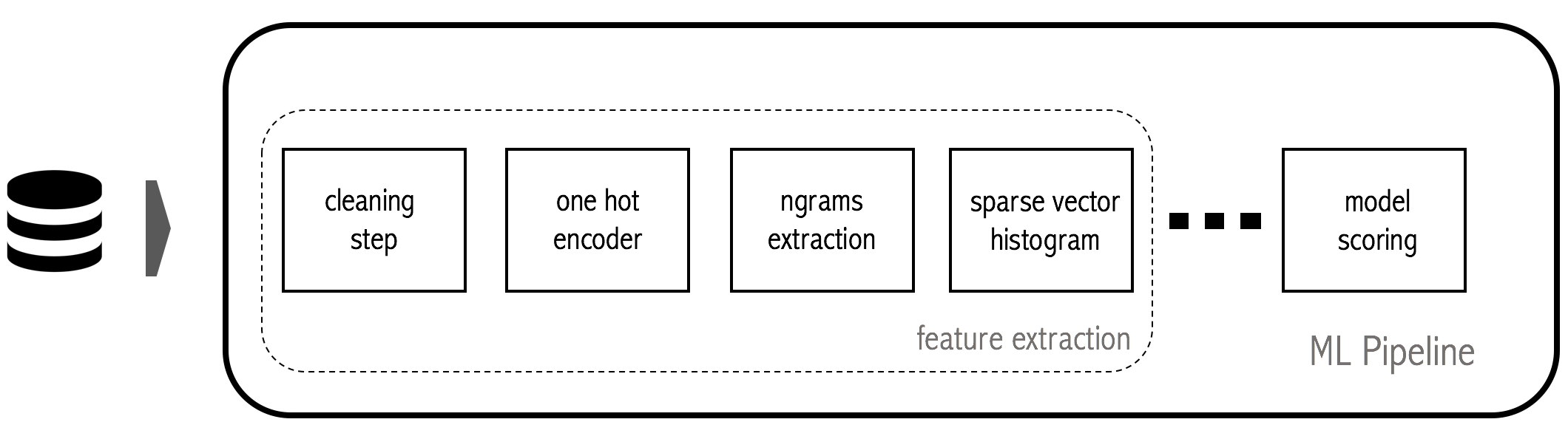

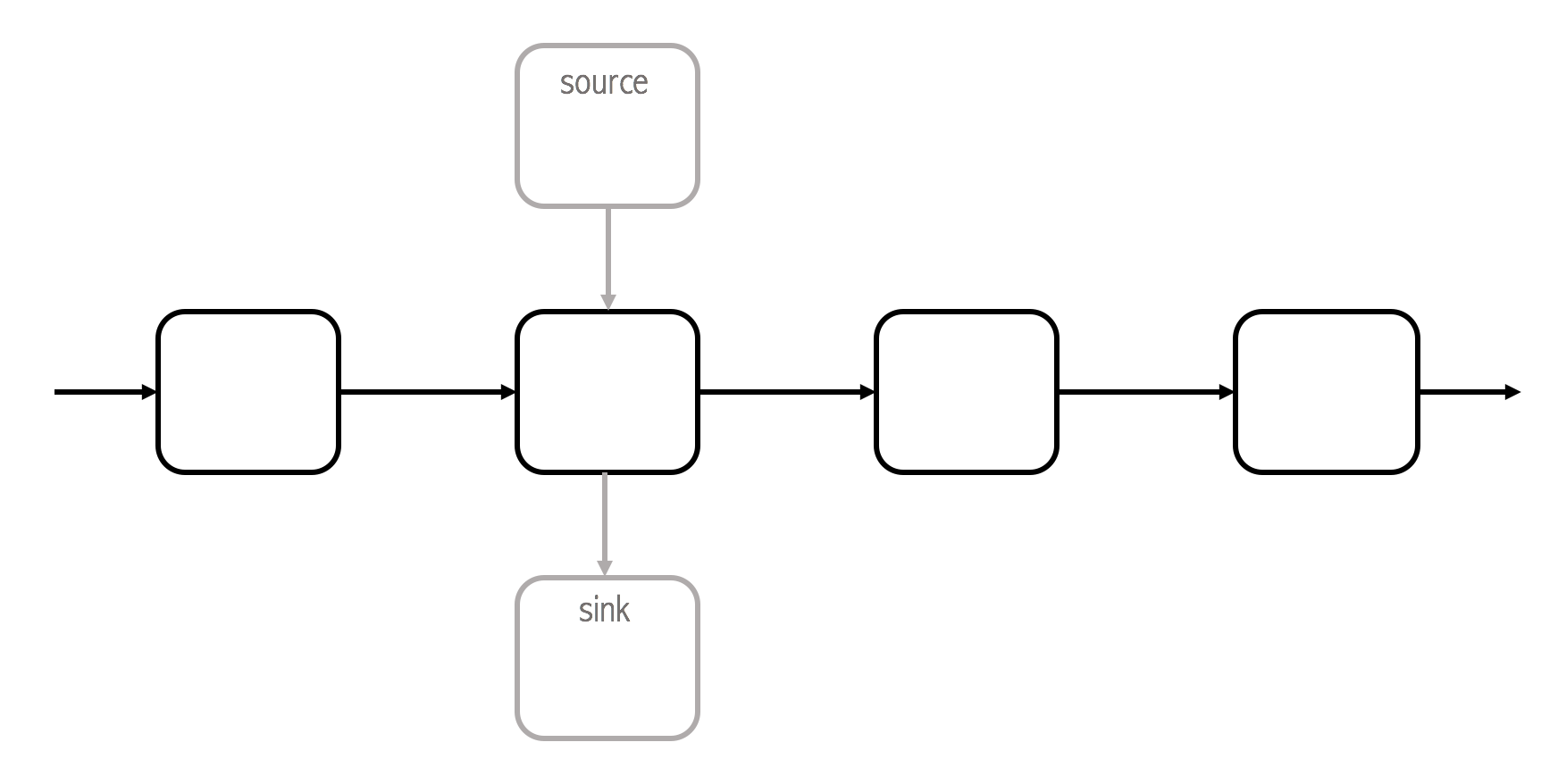

A general ML pipeline will have data streamed to it or pulled from storage. Once the data is ingested, a (possibly complex) set of transformations will extract useful information from this data, represent it in suitable form, and ask one (possibly more) model what it thinks about it.

Here is an illustration:

The problem

Typically these features are hand crafted through a (possibly long) process of trial and error. Once we are satisfied with the information, we must encapsulate all of these transformations into a pipeline that glues all of the small individual pieces.

The most trivial solution would be to just wrap all of the sequential transformations into another function, that we’ll accordingly call pipeline:

def pipeline(df, param1, param2, param3, param4, *_):

df_clean = clean_step(df, col=param1)

df_ohe = one_hot_encoder_step(df_clean, col=param2)

df_ngrams = ngrams_step(df_ohe, ngrams=param3)

df_sparse = sparse_repr_step(df_ngrams)

df_result = calculate_statistics(df_sparse, ['mean', 'avg', 'max'], col=param3)

return df_result

Besides the fact that we are perhaps centralizing the parameters (param1, param2) this style of code is still manageable.

It might however be hard to debug intermediary steps but still, testing is straightforward, given a data signal df we can apply pipeline(df) and confront the result with the expected one.

Data pipelining is, however, just the first concern. Proper abstractions should be aware of things like feature selection, hyperparameter tuning, model persistence among others.

Standard industry frameworks like scikit-learn or spark provide a Pipeline abstraction that assumes a programming model where the transformations are expressed through Estimators and Transformers. Data scientists are usually familiar with this model. An Estimator is used every time some pre-calculated data is necessary prior to the actual transformation, i.e. there is some training phase involved. A Transformer should hold all that is necessary to apply the computation. So a Estimator, once the training is done, will handover this pre-calculated data structure to the correspondent Transformer.

So we could take our previous steps, wrap them into a object that respects that Estimator/Transformer contract, and compose the pipeline.

However, I believe that the following change should come with a great of deal of pain:

def ngrams_step(df, n, col):

values = df[col].values.tolist()

df['ngrams'] = [list(zip(*[v[i:] for i in range(n)])) for v in values]

return df

to (assuming a scikit-learn pipeline):

from sklearn.base import TransformerMixin

from sklearn.pipeline import Pipeline, FeatureUnion

from functools import partial

class NGramsTransfomer(TransformerMixin):

def __init__(self, ngrams, col):

self.ngrams = ngrams

self.col = col

def transform(self, X, *_):

def ngrams_step(df, n, col):

values = df[col].values.tolist()

df['ngrams'] = [list(zip(*[v[i:] for i in range(n)])) for v in values]

return df

return ngrams_step(X, self.ngrams, self.col)

def fit(self, *_):

return self

or the equivalent in Spark:

from pyspark.ml.util import keyword_only

from pyspark.ml.pipeline import Transformer

from pyspark.ml.param.shared import HasInputCol, HasOutputCol

from pyspark.sql.functions import udf

from functools import partial

class NGramsTransformer(Transformer, HasInputCol, HasOutputCol):

@keyword_only

def __init__(self, ngrams, inputCol=None, outputCol=None):

super(NGramsTransformer, self).__init__()

kwargs = self.__init__._input_kwargs

self.setParams(**kwargs)

@keyword_only

def setParams(self, inputCol=None, outputCol=None):

kwargs = self.setParams._input_kwargs

return self._set(**kwargs)

def _transform(self, dataset):

def _find_ngrams(input_list, n):

return list(zip(*[input_list[i:] for i in range(n)]))

t = ArrayType(StringType())

out_col = self.getOutputCol()

ngrams = self.getNGrams()

input_col = dataset[self.getInputCol()]

find_ngrams = partial(_find_ngrams, n=ngrams)

return dataset.withColumn(out_col, udf(find_ngrams, t)(input_col))

NGramsStep = NGramsTransformer(inputCol=input_col, outputCol=output_col)

This is just way too much code to write, a liberalisation of the use of classes, adding entropy to the screen. The truth is that we are just interested in the data transformations. Testing has become more difficult, since now we need to create these objects and call transform on them. There is also a lot of boilerplate involved when wrapping our operations into the corresponding pipelining contexts by creating all these classes extending certain mixins. For instance, to provide persistence support to a custom spark model, the JavaMLReadable and JavaMLWritable traits should be mixed, in order to make available the required functionality.

One can however point some benefits with this approach. The side effects are now being managed by the pipeline layer, which can factor out common behaviour to deal with persistence to disk and error handling. This separation of concerns is highly desirable, since it helps reducing duplicate code and handles side effects in a more elegant way.

Relating back to our previous simple function approach, without using explicit classes, managing side effects creates problems:

def pipeline(df, param1, param2, param3, param4, *_):

if df.columns != [param1, param2, param4]:

raise Exception

df_clean = clean_step(df, col=param1)

df_ohe = one_hot_encoder_step(df_clean, col=param2)

# write intermediary steps

write_df('s3://pipeline/intermediary_ohe')

df_ngrams = ngrams_step(df_ohe, ngrams=param3)

df_sparse = sparse_repr_step(df_ngrams)

df_result = calculate_statistics(df_sparse, ['mean', 'avg', 'max'], col=param4)

# write final results

write_df('s3://pipeline/final')

return df_result

Again, testing has become considerably more difficult, because now we need to manage these side effects when testing. Readability of the code is also affected and generally this moves us away from our primary goal: just focus on data transformations.

How can we achieve the best from both worlds? Being able to write data transformations in their natural form, i.e. as plain functions, while keeping around an expressive context with abstractions that support the creation and managing of complex data transformation pipelines. The answer is to remain within the realm of functions, at least for the core part, and leave the creation of classes for the trivial stuff.

Our design should provide solutions for various problems. If at the end the list of requirements are not fulfilled in in its entirety , we should go back and restart our inquiring.

A possible solution

We propose now a minimalist thin layer to support the development of ML pipelines. It should be framework agnostic and assume very little about the user might want to do. The abstractions should provide a simple and effective way to manage complex machine learning workflows.

Desirable properties

-

Testability concerns should be addressed at the library design phase. The pipeline and associated components should be easily tested.

-

The caller should have complete control over the execution workflow. This is specially important for debugging, where we might need to probe the signal at an intermediary step for a closer inspection. A lazy execution mode should also be available for a finer execution control.

-

Side effects managing. Error handling and persistence are two important in a production environment and they should be handling at the library layer, which creates the opportunity to factor out behaviour common to all of the pipelines. The data scientist ideally should not need to worry about these boring details.

-

Templating. We should be able to start from a base pipeline and derive new ones by making changes to the parameters of the base computational description. A possible scenario of this feature in ML pipelines would be parameter tuning. You should be able to easily span new similar pipelines by applying small variations to a base one.

-

Self documenting. To share with other team members, or for more generic documentation purposes, the pipelines should ideally carry with them a description of the transformations being applied.

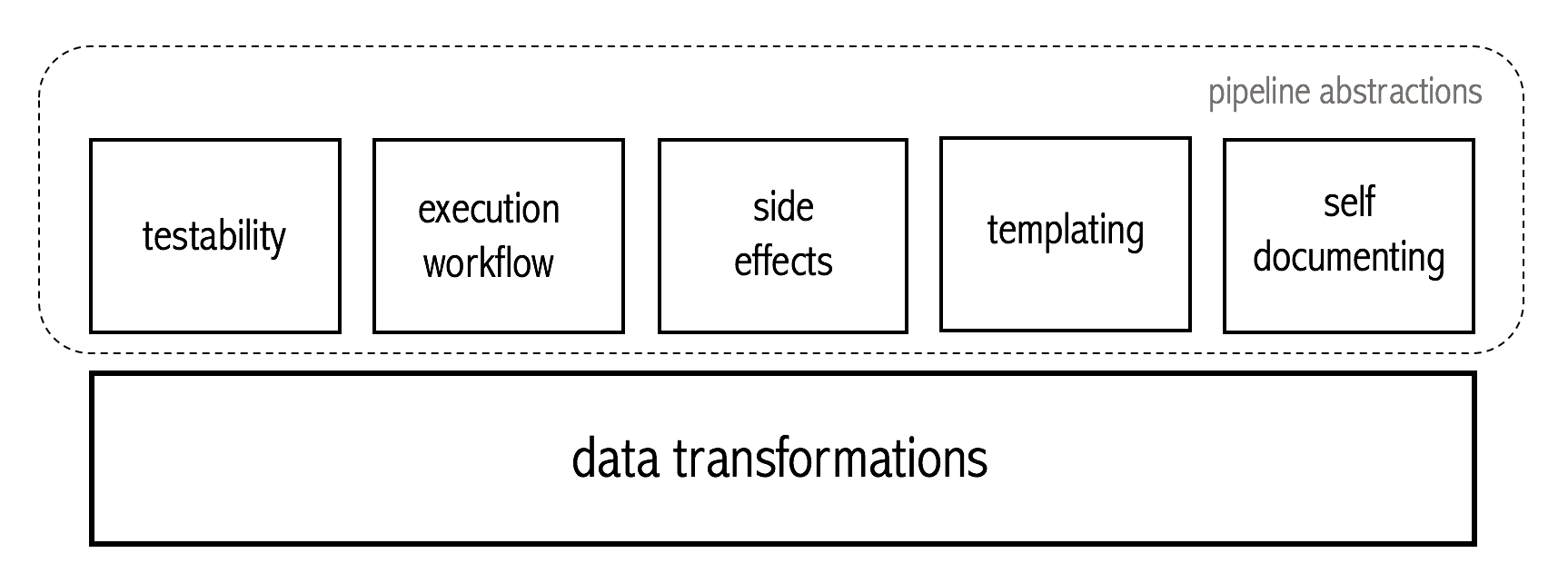

Visually, these are the different modules identified as desirable of the proposed pipeline design pattern.

Ideally, a data scientist should be focused almost entirely on the data transformations layer, defining simple, testable functions. These functions should then be effortless lifted to the pipelining context, which adds the required extra functionality, respecting the desirable design properties.

Another thing to keep in mind is that the development should be as declarative as possible. A good example is handling errors or invalid data. We should merely declare what conditions a signal must respect at a given node to be allowed to pass. Possibly a predicate of the form: (df: DataFrame -> Boolean). The details on how the validation is actually performed should be left to the library.

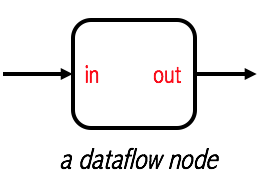

The proposed pattern is inspired in Dataflow programming, a programming model that can express well the composition of machine learning pipelines. We are using concepts of the most simple implementation of a dataflow system, Pipeline Dataflow. In these type of systems the fundamental computational unit is called node. The actual computations being performed, at any given node, are completely opaque to the dataflow system. Its primary concern is coordinating the movement of data. In this simplest form, a node only admits two ports, one for the input and another for the output. Again, this is very desirable since it naturally results in a framework-agnostic design.

Unix pipes are an example of a pipeline dataflow system. Is interesting to note that this same programming model can be also used for ML pipelines. Although simple, there’s a lot we can express with it.

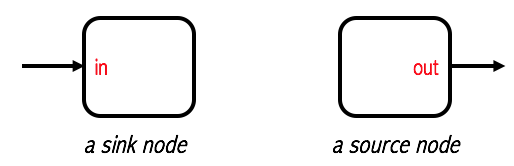

The pipelines abstractions provided by scikit-learn or spark are examples of implementations of Pipeline Dataflow systems. However they do not provide means of expressing general sink and source nodes.

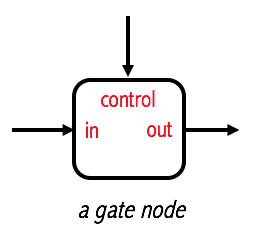

As suggested by their names, a sink node receives one or more inputs, but their return is completely ignored by the dataflow context. The most common use is to pass data to an system outside of the dataflow context, e.g. persisting data in to storage. From this short description, it is clear that this type of node is just useful for its side effects. On the other hand, a source receives nothing (at least from our context), but generates something that will be useful to the pipeline.

The introduction of generic nodes of this nature will be useful to provide extra functionality to support the operation of ML pipelines.

We need one more tool in our arsenal. A familiar construct from functional programming.

Currying

Very briefly, currying is a technique that allows us to incrementally pass arguments to a function g, instead of passing the whole argument list in one shot. Given a function of two arguments:

def g(a, b):

return a * b

If g is said to be curried, then the following condition must hold:

assert g(2)(2) == 4

g(2) necessarily needs to return a new function, that is expecting to receive a single argument, the still free parameter b. In Haskell for instance, every function is a curried function. This is not true for other programming languages. In the case of Python, we can go around and emulate a curry operator.

However, our implementation will be slightly different. In formal currying (arguably the only one), when a function g is curried, the application of one argument returns a new function f that is now expecting one less argument than the previous g. From our previous example, if we assume that g is curried, than g(2) returns a new function f whose behaviour would be necessarily equivalent to something like:

a = 2

def f(b):

return a + b

a is out of reach but still available for f to read it. We say that a is part of the closure that was returned when we called g(2).

In Python we will just emulate currying, and we will do this by not actually calling the original function. Instead, we will just keep saving the arguments that are being passed until we check that we are in conditions to call the function with all of the necessary arguments.

def func(a, b, c, d):

return a + b + c + d

In our implementation we will save the current bindings in a dictionary, hereafter called state.

| calls | state | can invoke func? |

|---|---|---|

| f(2) | {‘a’: 1} | false |

| f(2)(4, 10) | {‘a’: 1, ‘b’: 4, ‘c’: 10} | false |

| f(2)(4, 10)(1) | {‘a’: 1, ‘b’: 4, ‘c’: 10, ‘d’: 1} | true |

So once we have the full argument list bound, we call the original function. Otherwise we will keep saving them.

Additionally, in our case, we must support a rebind operation, i.e. changing the value of a previously defined argument. To understand this, we can just think in terms of the state in the previous table.

Let’s suppose the current state is {'a': 1, 'b': 4}. We still miss values for c and d to be able to invoke func, but in the meanwhile we will allow a rebind operation, e.g. we will be able for instance to move from a state {'a': 1, 'b': 4} to {'a': 100, 'b': 4} or to {'a': 10, 'b': 100, 'c': 1000}.

Although this moves us away from formal currying, is just a nice feature to have for tasks like parameter tuning, allowing us to take a default pipeline and change its default parameters, without actually running it.

So how do we achieve all of this? We will create a function, called curry, that will receive an arbitrary function func and return a new function that is a curried version of func.

def curry(func):

We will need to inspect the parameters of func, which contains useful information to manage our dictionary state.

signature = signature_args(func) # returns a list ['a', 'b', 'c', 'd']

Now we start defining the intermediary functions that will serve us the purpose of keeping track of the internal state.

def f(*args, **state):

if sum(map(len, [args, state])) >= len(signature):

return func(*args, **state)

Here we are checking if the number of arguments available matches are enough to satisfy the invocation of func. In case they do, we just call it. Note that this ensures that a function that goes through our curried operator, will exhibit the same original behaviour when called in a normal context.

If the combination of the positional args and state (the keyword arguments) is not sufficient to invoke func, we will keep them in scope and return a new function g:

def f(*args, **state):

if sum(map(len, [args, state])) >= len(signature):

return func(*args, **state)

def g(*callargs, **callkwargs):

pass

return g

Now regarding the implementation of g. Note that, in its body, g has access to the previous state and arg that are in the closure. Therefore, when invoked, it’ll have access to the current invocation parameters callargs and callkwargs as well as the previous ones arg and state.

So now let’s move to g’s body. Maybe it will be better to think of a practical example to explain g’s implementation.

def func(a, b, c, d):

return a + b + c + d

func = curry(func)

func(1, 2) # def g(*callargs, **callkwargs) is returned

func(1, 2) will return the function g of the previous snippet. At that moment, g will have access to the outer args = [1, 2] and state = {}.

If we now call it again, we will enter g’s body:

func(1, 2)(10, d=1) # calls g with callargs=[10] and callkwargs={'d':1}

What should our state at this point? Merging all the arguments should result in {'a': 1, 'b': 2, 'c': 10, 'd': 1}. So we should take all of the positional arguments available, i.e. args + callargs, check to which arguments in the original function they correspond to, and consider also the new keyword arguments callkwargs. By checking to which keywords the positional arguments correspond, we can always construct our current state. Here’s the implementation of g:

def g(*callargs, **callkwargs):

args_to_kwargs = {k: v for k, v in zip(_expected(func, state), args + callargs)}

newstate = {

**state,

**args_to_kwargs,

**callkwargs

}

if len(newstate) >= len(signature_args(func)):

return func(**newstate)

return f(**newstate)

So we move everything in the our internal state to be keyword-based (that’s what args_to_kwargs does). Once we translate positional arguments (args) to keyword arguments (kwargs), we construct the complete new state newstate. The rest is straightforward. If our state contains a correct number of arguments, we call the original function func with our current state. Otherwise we take a step back and return again f, now with the updated state.

This will keep going until we are in a position where len(newstate) >= len(signature_args(func)), i.e. we have all the required arguments. This is why this is just a curry emulation. We keep the original func aside, and just manage an internal state that will invoke the function when the necessary conditions are met.

Here’s everything together:

def curry(func):

signature = signature_args(func)

def f(*args, **state):

if sum(map(len, [args, state])) >= len(signature):

return func(*args, **state)

def g(*callargs, **callkwargs):

args_to_kwargs = {k: v for k, v in zip(expected(func, state), args + callargs)}

newstate = {

**state,

**args_to_kwargs,

**callkwargs

}

if len(newstate) >= len(signature):

return func(**newstate)

return f(**newstate)

return g

return f

signature_args can be a one-liner:

def signature_args(callable):

return list(inspect.signature(callable).parameters)

Now we have a function, curry, that receives a another function func and returns a curried version of it. To make use of it, we’ll follow the decorator pattern available in Python, see PEP 318. The decorator pattern provides a nice syntax to make use of higher order functions, i.e. functions that receive other functions as arguments.

It works in the following manner:

@decorator

def mul(x, y):

return x * y

decorator is just a function that will receive the function declared immediately after it, i.e. mul in this case, and returns something. Literally. It can return a humble integer:

def decorator(func):

return 2

@decorator

def mul(x, y):

return x * y

assert mul == 2

Not very useful though. Usually this pattern is used to return another function with extended functionality or to inject dependencies into the function arguments. We’ll make use of the decorator syntax to extend our pipeline functions with curry.

Quick test of the functionality:

@curry

def f(a, b, c, d):

return a + b + c + d

assert f(1)(2)(3)(4) == 10

assert f(1,2,3)(4) == 10

assert f(1)(2,3)(4) == 10

assert f(1, 1, 1)(a=1, b=1, c=3)(b=2)(4) == 9

This is however a simplified version, even a bit destructive. For instance, we are not propagating the original function static attributes, e.g. __name__ or __doc__:

def func(a, b, c, d):

return a + b + c + d

assert func.__name__ == 'func'

@curry

def func(a, b, c, d):

return a + b + c + d

assert func.__name__ == 'func' # fails

The last assertion fails since in this simplified version we are not propagating these attributes to the functions that are being created in the process.

Additionally this version doesn’t deal with functions that have default arguments. In the repository you can check the complete version.

Constructing ML pipelines

The curry-like operator we have just defined constitutes the core mechanism of the design pattern we are presenting. The full source code for this proof of concept is available in the repository. However, in this blog post we must proceed with our investigation and reason about the most beneficial way of constructing ML pipelines. Namely which features should be available and what properties the abstractions must respect if we were to be users of the library. A simple example will be useful to guide us.

We’ll be making use of pandas and scikit-learn for this illustration. But first we need some data to work with:

| name | age | score | language | exam(min) | feedback-questionnaire | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Bob | 30 | 100 | python | 120 | AABB |

| 1 | Joe | 17 | 110 | haskell | 90 | BACB |

| 2 | Sue | 29 | 170 | Python | 90 | AABA |

| 3 | Jay | 20 | 119 | JAVA | 110 | BBCC |

| 4 | Tom | 38 | 156 | java | 100 | ACCB |

Let’s suppose this is the data available for a (rather dubious) recruitment process. The data needs to be cleaned and some features extracted. We’ll be in charge of assembling a transformation pipeline to prepare this data for model scoring. The transformations will consist of some simple data cleaning tasks along and some steps to extract features from numerical data as well as from text data.

For now we have two requirements:

-

We want to express our transformations in their natural form, as functions, without a need to wrap them in some class.

-

Logically related transformation steps should be allowed to be replaced by an abstraction that represents their composition.

First, we need a way of lifting a function to our dataflow context. Much in the way as the TransformerMixin and Transformer traits fulfil the contract requirements to create pipelines in scikit-learn and spark, respectively. We want to be able to do it by means of a just a decorator.

Our pipeline will start with two simple cleaning steps.

@node()

def step_lowercase(df, col):

"""

Converts all the strings of 'col' to lowercase.

"""

df.loc[:, col] = df.language.map(str.lower)

return df

@node()

def step_filter_numeric(df, col, threshold):

"""

Filters all rows whose value in 'col' < 'threshold'

"""

return df[df[col] > threshold]

We lift the functions by marking them with node. Furthermore the decorator shouldn’t be destructive, i.e. the function is to be used exactly in the same way outside of our context.

Then we have two steps that extract features from text data:

from sklearn.preprocessing import LabelBinarizer

@node()

def step_dummify(df, col, outputcol, sparse=False):

"""

Binarize labels in a one-vs-all fashion.

By default the return is given in a dense represententation.

If a sparse representation is required, set sparse='True'

"""

enc = LabelBinarizer(sparse_output=sparse)

enc.fit(df[col])

df.loc[:, outputcol] = pd.Series(map(str, enc.transform(df[col])))

return df

@node()

def setp_satisfaction_percentage(df, col, outputcol):

"""

A satisfatory answer is assumed by a "A" or a "B"

"C" represents an unsatisfactory asnwer.

perc = ["A" || "B"] / # questions

"""

df.loc[:, outputcol] = df[col].apply(lambda x: len(x.replace("C", ""))/len(x))

return df

To finish we address the numerical columns with two more steps:

from sklearn.preprocessing import StandardScaler

from sklearn.preprocessing import MinMaxScaler

@node()

def step_standard_scale(df, col, outputcol, with_mean=True, with_std=True):

"""

Standardize features by removing the mean and scaling to unit variance of 'col'

Standardization of a dataset is a common requirement for many machine learning estimators:

they might behave badly if the individual feature do not more or less look like standard normally distributed data

(e.g. Gaussian with 0 mean and unit variance).

'with_mean': If True, center the data before scaling.

'with_stf': If True, scale the data to unit variance (or equivalently, unit standard deviation).

"""

scaler = StandardScaler(with_mean=with_mean, with_std=with_std)

scaler.fit(df[col].reshape(-1, 1))

df.loc[:, outputcol] = scaler.transform(df[col].reshape(-1, 1))

return df

@node()

def step_scale_between_min_max(df, col, outputcol, a=0, b=1):

"""

Transforms features by scaling each feature to a given range.

The range to scale is given by ['a', 'b]. Default [0, 1].

"""

scaler = MinMaxScaler(feature_range=(a, b))

scaler.fit(df[col].reshape(-1, 1))

df.loc[:, outputcol] = scaler.transform(df[col].reshape(-1, 1))

return df

To bundle together a set of logically related steps we need something like a Stage abstraction, to be constructed in the following way:

stage_cleaning = Stage("cleaning-stage",

step_dummify(col="language"),

step_filter_numeric(col="age", threshold=18)

)

Notice that we are making use of our curry operator. We are locking the parameters that parameterize the behaviour of each step but we are leaving the data signal df as a free variable that will have its value injected at the proper time.

The remaining two stages:

stage_text_features = Stage("process-text-features",

step_lowercase(col="language")(outputcol="language-vec")(sparse=False),

setp_satisfaction_percentage(col="feedback-questionnaire", outputcol="satisfaction-percentage")

)

stage_numerical_features = Stage("process-numerical-features",

step_standard_scale(col="language", outputcol="language-scaled"),

step_scale_between_min_max(col="exam(min)", outputcol="exam(min)-scaled")(a=0, b=1)

)

A second level of abstraction, Pipeline, should be allowed. This will provide better semantics when creating a pipeline.

pipeline = Pipeline("feature-extraction-pipeline",

stage_cleaning,

stage_text_features,

stage_numerical_features

)

Self documenting

Adding a description for documentation purposes:

pipeline = pipeline.with_description("recruitment process data preparation for model scoring")

The objects should be self-documenting, in a way that we can promptly assess them and have a general understanding of the work they are performing.

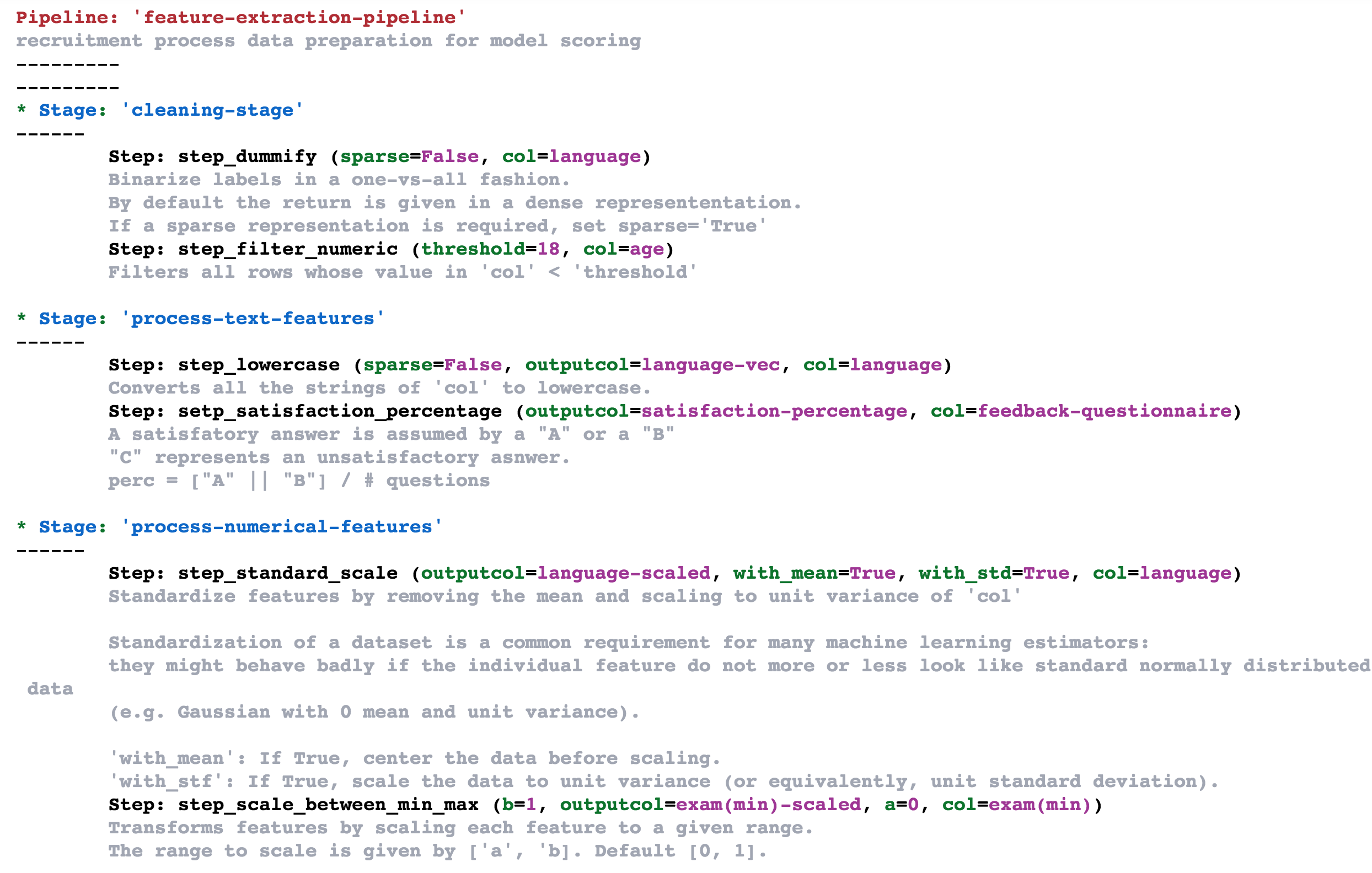

>>> pipeline

All the arguments of each step that are currently locked should be presented in the screen with their current value.

Execution workflow

To trigger the execution of the pipeline, a data signal is needed. Moreover, the caller should have complete control over the execution workflow.

We should be able to run it end to end:

result = pipeline.run(df)

A specific step:

df_result = pipeline.run_step(df, 'step_a')

Or run from the beginning until the specified location.

df_result = pipeline.run_until(df, 'stage preprocess/step_a')

Every step should just be computed in lazy way, where the computations are just actually performed when the result is needed. If this is true, then we can have a generator that represents the whole execution of the pipeline, step by step.

gen = pipeline.run_iter_steps(df)

df_intermediary_1 = next(gen)

df_intermediary_2 = next(gen)

df_intermediary_3 = next(gen)

A similar functionality should be available to provide control to the caller at the stage level. These are useful specially in debugging phases to track wrong behaviours.

Templating

The pipeline design should strive for modularity and reusability. In this view, we should be able to use pipelines as templates, serving as a base for a more custom behaviour.

At construct time, the steps composing the stage are normally bound to operate under certain parameters This bindings should be allowed to be modified by passing a configuration with the new intended values.

To exemplify, suppose that we want to change the representation of the one hot encoding step to a sparse one instead of the current dense one. Furthermore we want to change the scale of the exam(min) column to [0, 10].

changes = {

'cleaning-stage': {

'step_dummify': {

'sparse': True

}

},

'process-numerical-features': {

'step_scale_between_min_max': {

'a': 0,

'b': 10

}

},

}

pipeline_ = pipeline.rebind(changes)

An operation like rebind should perform just the needed modifications to the pipeline to accommodate the new required changes.

Furthermore every operation of done over our abstractions should be done in an immutable fashion. Newly created objects must always be returned. Even for simple operations like with_description.

Simple composition primitives should also be available:

p.andThen(q) # returns a new pipeline equivalent to q(p)

p.compose(q) # returns a new pipeline equivalent to p(q)

General side effects

The computational model define by our dataflow system should allow the addition of arbitrary sink and source nodes.

There are computational steps that have dependencies. Consider a step that normalizes a column between 0 and 1. In a production environment, these steps need to have available some pre-calculated data, in this case the maximum and minimum of the seen values for that column. Otherwise the step cannot know the range of the data. We realize then that are some steps that will need to make some calculations over the full historical dataset, i.e. a training phase. If this is true, then it follows that a pipeline should be able to run in two different modes:

-

the default one, where dependencies are not being watched, they should be provided at call time, or injected if there are available handlers (source nodes) for the dependencies required (check above fig). If handlers are not available, the dependencies will need to be calculated from the current data.

-

a fit mode that will watch the steps outputs in order to save the pre-calculated data. A handler (a sink node) must be given for each dependency. This handler will capture the dependency and is free to do anything with it.

Sink and source nodes can be used to manage the dependencies of each step.

In order to do so, we need to modify a bit the steps that have dependencies to the following form:

@node()

def step_dummify(df, col, outputcol, sparse=False, label_binarizer: None):

"""

Binarize labels in a one-vs-all fashion.

By default the return is given in a dense represententation.

If a sparse representation is required, set sparse='True'

"""

if not label_binarizer:

enc = LabelBinarizer(sparse_output=sparse)

enc.fit(df[col])

df.loc[:, outputcol] = pd.Series(map(str, enc.transform(df[col])))

return df, label_binarizer

So now each step, that needs its dependencies managed, will have to receive them by argument. If they are available, the dataflow context will inject them (via a source node). If not, they should be calculated and then returned by the node to be handled (via a sink node).

To register source/sinks handlers for each dependency we just need to create a dict with an entry for every dependency a step has.

dependencies = {

"label_binarizer": [loader(path), writer(path)]

}

Both loader and writer should be lazy functions, so that we are able to lock in the necessary parameters, e.g. path, without actually invoking the function. There should be a helper decorator to perform exactly this:

@lazy

def loader(path):

with open(path, 'rb') as f:

return pickle.load(f)

@lazy

def writer(path, model):

with open(path, 'wb') as f:

pickle.dump(model, f)

We could then pass these handlers to the lifting decorator:

@node(dm=dependencies)

def step_dummify(df, col, outputcol, sparse=False, label_binarizer: None):

"""

Binarize labels in a one-vs-all fashion.

By default the return is given in a dense represententation.

If a sparse representation is required, set sparse='True'

"""

if not label_binarizer:

enc = LabelBinarizer(sparse_output=sparse)

enc.fit(df[col])

df.loc[:, outputcol] = pd.Series(map(str, enc.transform(df[col])))

return df, label_binarizer

Now this step has one source/sink pair handling the LabelBinarizer dependency.

Furthermore we should be able to load all of the registered dependencies of a pipeline (calling all of the source nodes):

pipeline_ = pipeline.lock_dependencies()

By making use of currying, a new pipeline should be derived by rebinding all of the dependencies for each step (by making use of the rebind operator).

On the other hand, we should have a way of running the pipeline while ensuring that the sink nodes will be called. fit is an appropriate name in this case.

pipeline.fit(df)

When running in fit node, the calculated dependencies are passed to the respective sink nodes, that can execute arbitrary code, e.g. persisting on disk.

Just with the use of functions we could create a mechanism to manage step’s dependencies.

Validations

When a data scientist is writing transformations, is not obvious which exceptions should be raised in case the input signal does not meets the requirements. Validation should be lifted to the dataflow layer, at leats for the more imperative part of it.

Each step should be able to receive a set of constraints which the input signal must respect in order to proceed the execution flow. Each constraint should be a predicate of the form (InputSignal) -> Boolean.

Given some validations:

def has_language(df):

return 'language' in df.columns

def has_min_size(df):

return df.shape[0] > 100

We should be able to add validations to any node

@node(val=[has_language, has_min_size])

def step(df, col):

pass

This is a form of a gate node

This node controls the passage of a signal to a certain node. If the validation check fails, the signal is blocked.

Conclusion

The purposed design pattern makes minimal use of classes. Just two in fact: Stage and Pipeline, which are merely used for keeping together computations that are logically related. Everything else is done using functions which highly facilitates testing and makes the code more readable and manageable.

Keeping data transformations in their natural form, as functions, bring us one step closer to our desired goal: just focus on the data transformations. Also the fact that each computational node, by definition, performs an opaque transformation, leads to a design that is naturally framework-agnostic.